A friend who practises calligraphy recently offered to gift me a piece of his work. He asked what I’d like him to write, and I said, “Only with wine.” He asked what it meant. I smiled and explained it’s from The Short Song: “What can dispel sorrow? Only wine.” For me, wine has grown increasingly important.

Because we are all drinkers.

"Do you often drink alone?" she asked.

"Yes."

"To forget painful memories?"

"To forget the joy of memories."

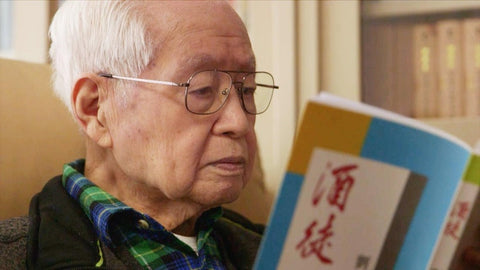

The first time I read The Drunkard, I was captivated by Liu Yichang’s prose. If his writing were a cocktail, it would be an exquisite blend of wistfulness, nostalgia, solitude, and melancholy—perfectly measured. The pacing is unhurried, much like the films of Wong Kar-wai, which are unmistakably inspired by Liu’s style.

I had planned to write about Wong’s films one by one, given how much I admire them. But when news of Liu’s passing reached me, I felt compelled to pause and bid him farewell, even if this humble page seems an inadequate place for such a gesture.

It wasn’t until I was twenty-three or twenty-four that I truly fell in love with In the Mood for Love. Some works—like certain emotions—require lived experience to fully grasp. Of course, my own experiences were far less elegant and tangled than those in the film. That summer, I watched it multiple times, discovering new details with each viewing and reinterpreting the protagonists’ emotions anew.

I once read a review suggesting that Chow Mo-wan’s interactions with Su Li-zhen were motivated by revenge, evident in his gaze and his choice of ties. At first, I dismissed the idea as impossible. Watching again, I thought it had merit. By the third viewing, I still couldn’t believe it—though not because it wasn’t plausible, but because I didn’t want to believe it. If the film were reduced to nothing but seduction, calculation, and unreciprocated feelings, it would feel like such a waste.

"To add colour to old memories is something I often do these days."

This line from Intersection remains one of my favourites. Perhaps that’s why I write—to add colour to memories, adjusting their shades, weights, and textures. Through words, I shape past people and stories into forms I find beautiful. It’s a kind of quiet joy.

In 2046, Chow remarks:

"Sometimes I feel the world has grown absurd. I used to write novels for one person, but now I write to keep myself from starving, for all the bored people out there. Once, two passionate people avoided each other at all costs; now, two passionless people strive desperately to connect. Perhaps only wine can reignite my passion. Wine is a marvellous thing."

I came to The Drunkard much later than In the Mood for Love. As a child, I couldn’t drink, and as a young adult, drinking was simply a social activity. But now, I understand what Liu meant when he wrote, “Wine becomes a passport, often taking me to another world.” I rarely drink to excess; I prefer that perfect state of mild intoxication where the world’s temperature and humidity shift ever so slightly. In Wong Kar-wai’s films, I sense a similar atmosphere, a world just adjacent to ours.

"All memories are damp."

I used to think 2046 was far inferior to In the Mood for Love, largely because I didn’t care for the performances of Carina Lau and Takuya Kimura. They felt unnatural, out of place. But rewatching it on a flight yesterday, I realised everything was just as it should be. It wasn’t the film that lacked maturity—it was me. Time has aged me a few years, and now I see its brilliance. Love, the film reminds us, is tied to time. The same could be said for appreciating art and literature.

Liu Yichang lived nearly a full century, witnessing wars, upheavals, and the loss of countless loved ones. To endure all of that is no small feat. Thank you, Mr. Liu—the real-life Chow Mo-wan. May you rest well, and may your words remain with us always.

Because we are all drinkers. In those moments of gentle intoxication, I will think of you. Cheers.

Let’s raise a glass with Kenny Chesney’s Good Stuff, a song about wine, love, and life.